How Bloom Filters trade perfect accuracy for incredible speed and efficiency.

Imagineh2

You are building the signup page for the next big social network. You have 500 million existing users. A new user types in cool_dev_69. Your backend has to answer one question immediately:

Is this username already taken?

Here are your terrible options:

The SQL Query: You run SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = 'cool_dev_69'. The problem: This hits the disk. Disk is slow. If 10,000 people sign up at once, your database locks up.

The RAM Hog: You load all 500 million usernames into a Hash Set in memory. The problem: Strings are heavy. 500 million usernames might cost you 30GB+ of RAM just for a simple check. That’s expensive.

You are stuck between “too slow” and “too expensive.”

You need a third option. You need a data structure that uses almost zero RAM, returns an answer in nanoseconds, and never misses a taken username.

Enter the Bloom Filter.

The “Napkin Math” Solutionh2

In 1970, Burton Bloom came up with a probabilistic data structure that essentially said:

“I can’t tell you if something is definitely there, but I can tell you if it’s definitely NOT there.”

It sounds useless, right? Why would you want a system that only knows half the answer?

Because in computing, “Definitely Not” is the most valuable sentence in the English language. It allows you to skip expensive operations.

How It Works (Without the Boring Parts)h2

Forget complex trees or linked lists. A Bloom filter is just a bit array—a long row of boxes that can only hold a 0 or a 1. Initially, they are all 0.

To add an item (let’s say, the string “Google”), you don’t store the word “Google.” That takes up too much space. Instead, you run it through a few hash functions.

Think of a hash function as a blender. You throw “Google” in, and it spits out a few numbers based on the “ingredients” of the word.

- Hash 1 says: Position 37

- Hash 2 says: Position 12

- Hash 3 says: Position 16

You go to your bit array and flip the switches at 37, 12, and 16 to 1.

That’s it. You have effectively taken a “fingerprint” of the data without storing the data itself.

Say you add multiple different values now: each of these values is run against these 3 hash functions and sets the bit if it is not set (if it is set - let it remain set).

Assume you haven’t added ‘Oracle’ yet and the different bits set till now are 37, 12, 16, 19, 45, 72 etc.

The “Lie” (Collision)h2

Now, let’s say you want to check if “Oracle” is in the set. You hash “Oracle”. The blenders give you: 19, 12, 15

(bruh → oracle wasn’t added yet though right?)

Now use better - non probabilistic read to verify.

But say you wanna check netapp → 37, 12, 9

(9 is not set)

Voila! DEFINITELY NOT THERE

The Golden Rule of Bloom Filtersh2

Bloom filters operate on a strict moral code:

False Positives are allowed: It might say “Yes” when the answer is “No.” (We waste a little time checking).

False Negatives are forbidden: It will never say “No” when the answer is “Yes.” (We never lose data).

This asymmetry is what makes them perfect for databases. If the filter says “No,” the database can safely skip the disk read because it knows the data isn’t there.

Real World Sightingsh2

You use Bloom filters every day without knowing it.

Medium: When you visit Medium, they have to recommend articles you haven’t read. Checking your “read history” against millions of articles is slow. They use a Bloom filter to filter out the “definitely read” ones first.

Google Chrome: Chrome used to contain a local Bloom filter of malicious URLs. Before the browser asked a remote server “Is this site safe?”, it checked the local filter. If the filter said “No,” the site was safe. If “Maybe,” it did the network call.

Cassandra & HBase: These databases write files to disk specifically so they don’t have to load them. They check a Bloom filter header before opening the file. If the filter returns negative, they don’t even touch the hard drive.

The Math of Uncertaintyh2

You might be wondering, “How big should I make the array to avoid lies?”

There is an elegant equation for this. If you expect items and want a false positive probability of , the size of your bit array should be:

Rough translation: For a 1% error rate, you need about 9.6 bits per item.

That is incredibly efficient. You can store the existence of a million items in roughly 1.2 MB of RAM.

The Bottom Lineh2

Bloom filters teach us a valuable lesson in engineering: Perfection is expensive.

Sometimes, you don’t need the perfect answer. You just need to filter out the obvious noise so you can focus your expensive resources on the things that might actually matter.

They are the “Maybe” pile of computer science—fast, space-efficient, and slightly dishonest. But they make the web feel instantaneous, so we forgive them.

Simple Codeh2

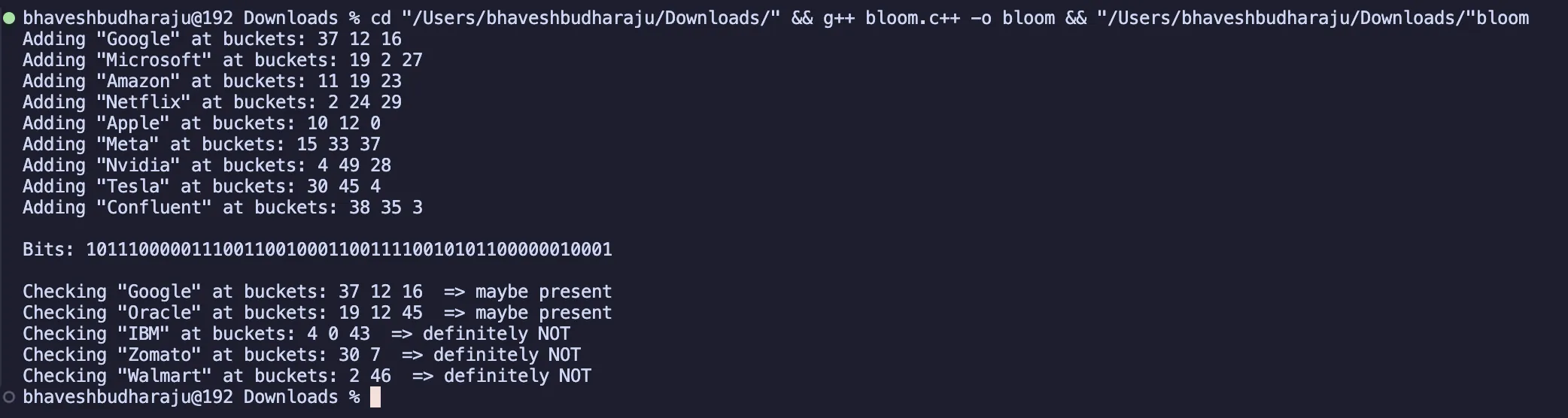

#include <iostream>#include <vector>#include <string>#include <functional>

using namespace std;

class BloomFilter {public: int size; int hashCount; vector<bool> bits;

BloomFilter(int size=50,int hashCount=3){ this->size=size; this->hashCount=hashCount; bits.assign(size,false); }

int hashWithSeed(const string& s,int seed){ hash<string> hasher; string combined=s+to_string(seed); unsigned long h=hasher(combined); return (int)(h%size); } void add(const string& item){ cout<<"Adding \""<<item<<"\" at buckets: "; for (int i=0;i<hashCount;i++){ int h=hashWithSeed(item,i); bits[h]=true; cout <<h<<" "; } cout<<endl; }

bool check(const string& item){ cout <<"Checking \""<<item<<"\" at buckets: "; for (int i=0;i<hashCount;i++){ int h=hashWithSeed(item,i); cout <<h<<" "; if(!bits[h]){ cout <<" => definitely NOT\n"; return false; } } cout<<" => maybe present\n"; return true; }

void printBits() { cout<<"\nBits: "; for (int i=0;i<size;i++)cout<<bits[i]; cout<<"\n\n"; }};

int main() { BloomFilter bf;

bf.add("Google"); bf.add("Microsoft"); bf.add("Amazon"); bf.add("Netflix"); bf.add("Apple"); bf.add("Meta"); bf.add("Nvidia"); bf.add("Tesla"); bf.add("Confluent");

bf.printBits();

bf.check("Google"); // present bf.check("Oracle"); bf.check("IBM"); bf.check("Zomato"); bf.check("Walmart");

return 0;}

Comments