A deep dive into Git internals, rewriting commit metadata, and why Git lets you forge history.

TL;DRh2

I rewrote an old Git commit to make it look like Batman authored it in 2004. Git fully accepted it. GitHub displayed it. Git metadata is editable, rewriting history changes commit hashes, and force-pushing removes Verified badges.

A friend and I got into one of those random tech arguments — nothing serious, nothing life-changing — but somehow it turned into:

“Bro, you cannot change old Git commits like that. That’s the whole point of version control — you can’t rewrite the past.”

I was confident. I was wrong.

And that wrong confidence pushed me into a rabbit hole where I ended up rewriting Git commit metadata, changing author names, setting dates from before I even existed, and learning way too much about how Git actually works under the hood.

It started innocently. We were talking about Git’s SHA-1 hashing and how each commit depends on its parent, forming an immutable chain. I was busy explaining how “cryptographically secure” it all is…

…and then I learned you can change all of it.

This blog is the story of that experiment — how I modified a commit to look like it was authored by Batman on October 18, 2004, why Git lets you do this madness, and what the consequences are.

The Commit I Wanted to Rewriteh2

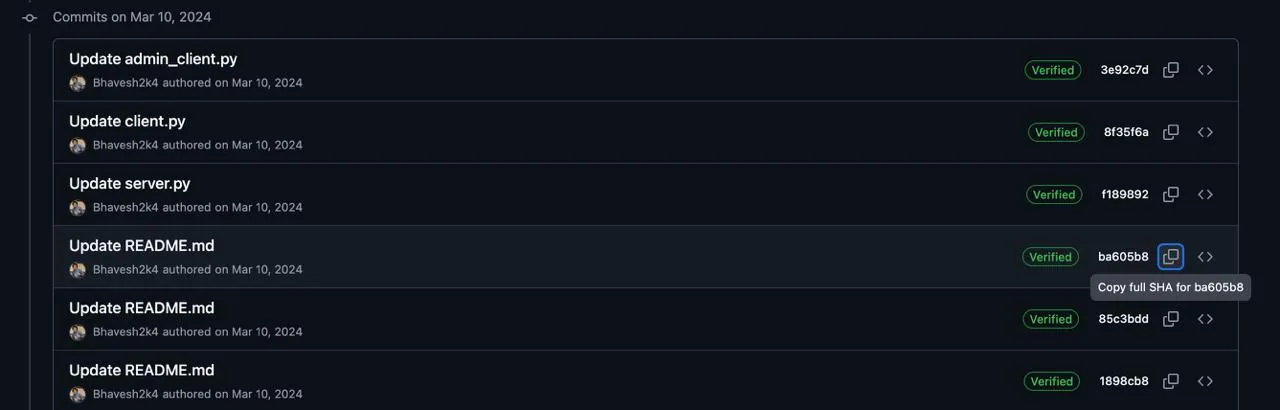

I started with this real commit:

ba605b88a23a7458e2cb3caeb839ea10376e3efb

It was a normal, boring commit:

- authored by me

- on March 10, 2024

- fully Verified by GitHub (signed)

I didn’t want to change the code. I wanted to change the metadata — author, date, everything.

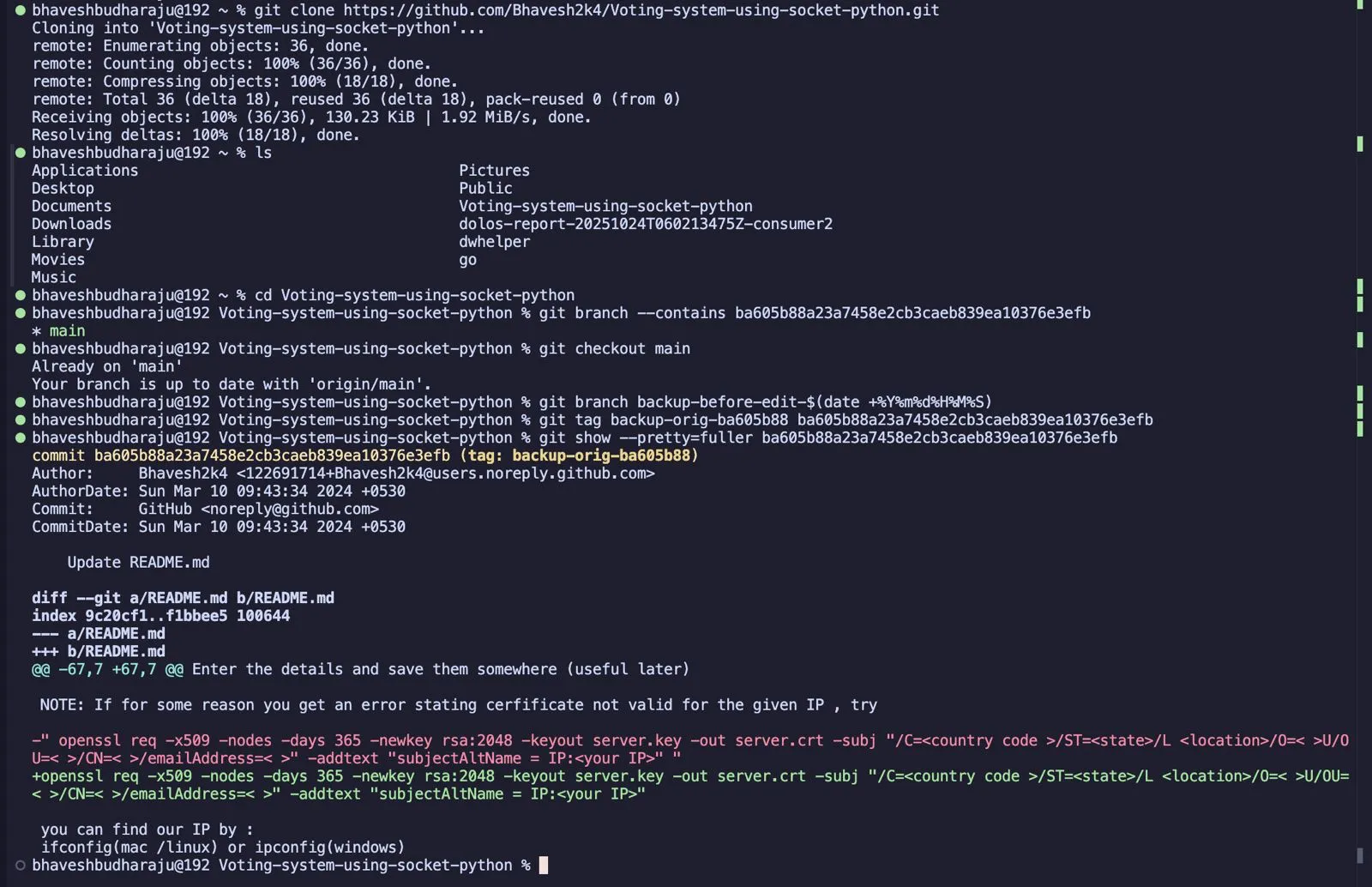

Before starting, I created a backup branch:

Step 1 — Stop at That Commit Using Interactive Rebaseh2

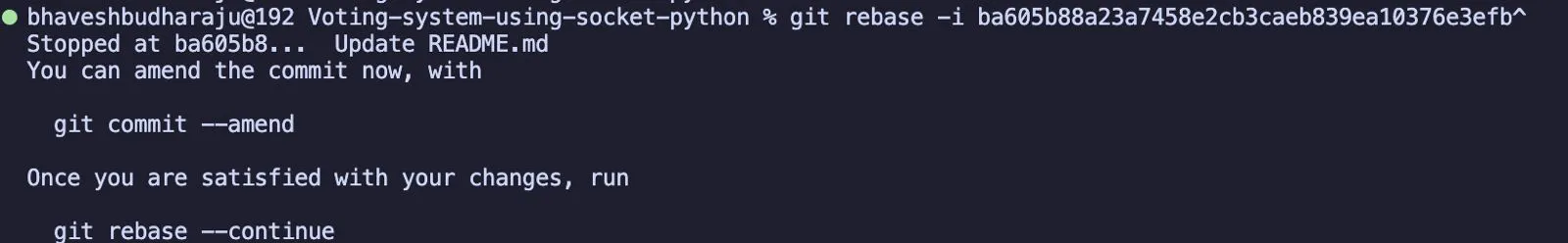

To rewrite an old commit, I ran:

git rebase -i ba605b88a23a7458e2cb3caeb839ea10376e3efb^The ^ means “one commit before this one.”

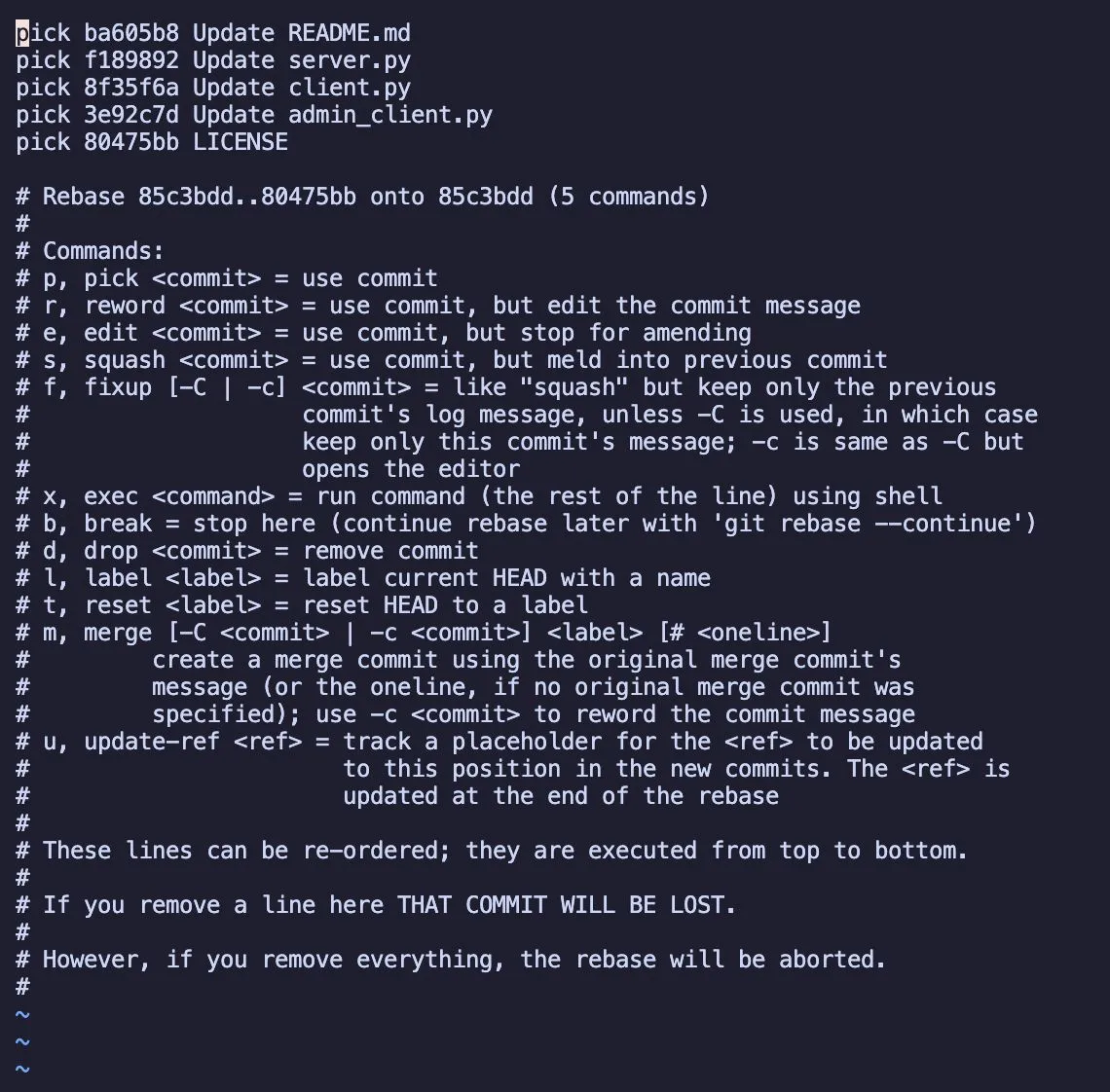

Git opened an editable list:

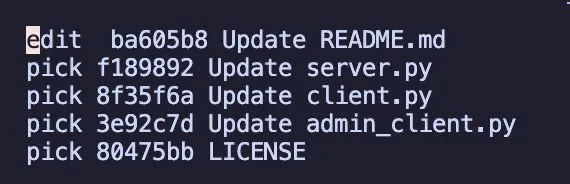

I changed pick to edit:

Saved the file, quit, and Git paused the rebase exactly on that commit.

Step 2 — Rewrite the Commit Metadatah2

Now for the fun part.

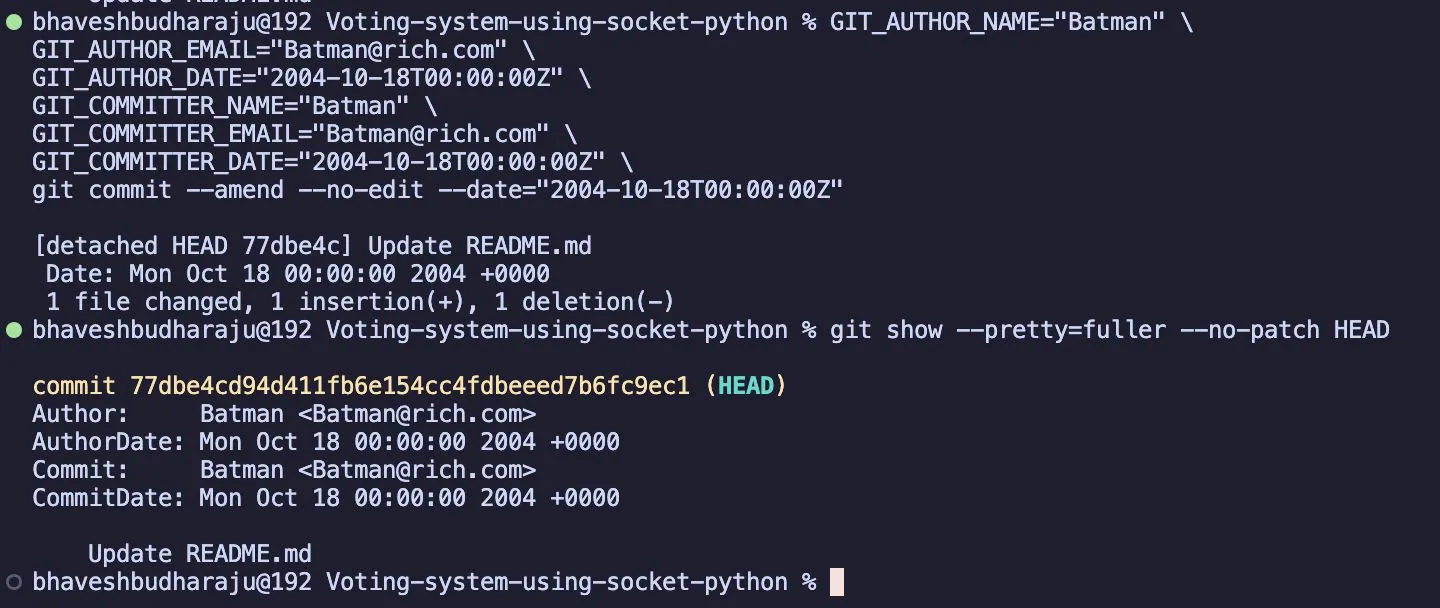

I changed everything:

- Author → Batman

- Email → Batman@rich.com

- Date → October 18, 2004

One command rewrites the entire commit identity:

GIT_AUTHOR_NAME="Batman" \GIT_AUTHOR_EMAIL="Batman@rich.com" \GIT_AUTHOR_DATE="2004-10-18T00:00:00Z" \GIT_COMMITTER_NAME="Batman" \GIT_COMMITTER_EMAIL="Batman@rich.com" \GIT_COMMITTER_DATE="2004-10-18T00:00:00Z" \git commit --amend --no-edit --date="2004-10-18T00:00:00Z"Git now genuinely believed Batman updated my README in 2004.

Step 3 — Continue the Rebaseh2

git rebase --continueThen I force-pushed the rewritten history:

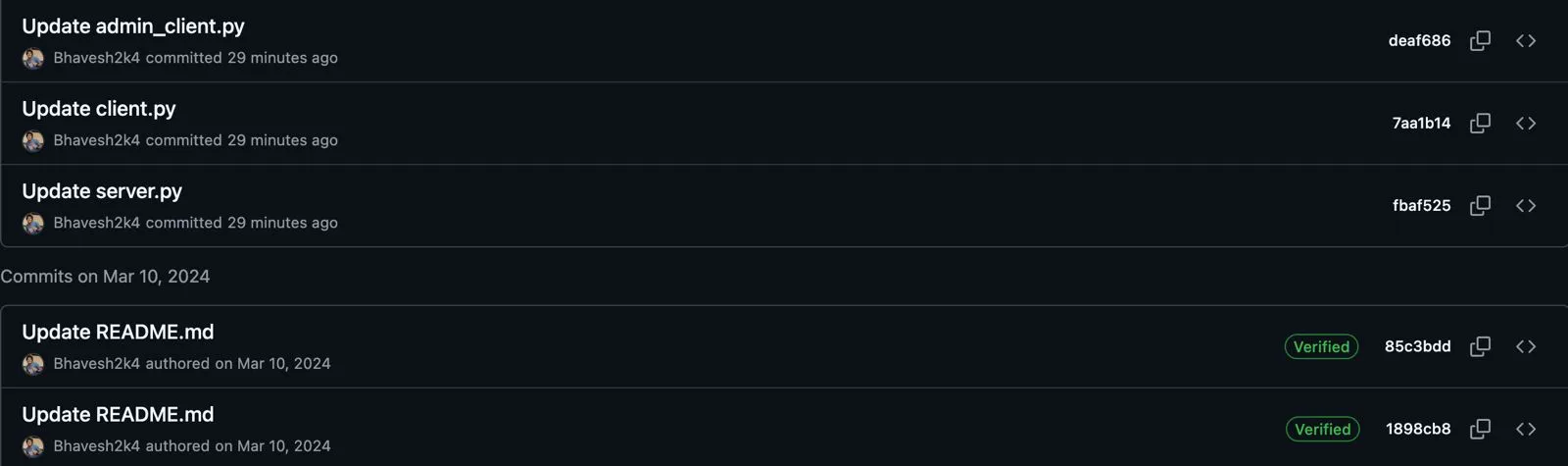

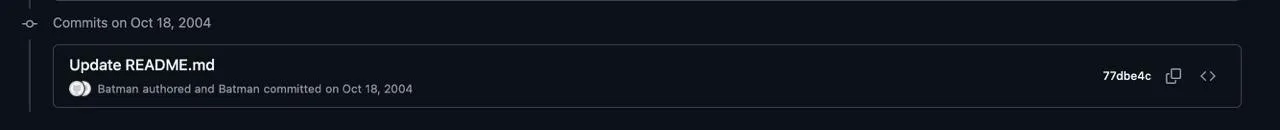

git push --force-with-leaseAnd suddenly GitHub displayed: Batman authored and committed on Oct 18, 2004 …with a brand-new commit hash.

Why the Commit Hash Changedh2

This was my favorite part.

Git commit hashes aren’t random. They’re SHA-1 hashes of:

- the author

- the committer

- the timestamp

- the commit message

- the entire tree snapshot

- the parent hash

If you change anything — even one character — Git generates a completely different hash.

So the original:

ba605b8...

became:

77dbe4c...

This is normal. Git is a content-addressable store, not a “timestamp recorder.”

Why Git Lets You Rewrite Historyh2

After losing the argument, the obvious question was:

Why does Git even allow this? Isn’t it supposed to be secure?

Turns out Git is designed to be flexible — aggressively flexible.

Here’s why.

1. Git trusts the user completelyh3

Git assumes you’re a responsible adult.

If you rewrite your history into chaos, that’s your problem.

2. Git was created for emailing patchesh3

In the early days, maintainers routinely:

- cleaned up commit messages

- fixed authorship

- edited timestamps

- squashed random messy commits

So rewriting was expected.

3. Metadata is just texth3

Name? Email? Timestamp?

Git doesn’t validate any of it.

You can literally run:

--author="Elon Musk <mars@spacex.com>" --date="1970-01-01T00:00:00Z"Git won’t blink.

4. Git prioritizes flexibility, not immutabilityh3

Git is not a blockchain.

Its philosophy is:

“Your repo, your rules.”

It gives you powerful tools — and enough rope to hang yourself.

The Dangers of Rewriting Historyh2

With great power comes great potential to destroy your team’s sanity.

Here’s what rewriting history can break:

1. Collaborationh3

If teammates have already pulled the old commits, rewriting creates merge hell.

2. Lost datah3

Git does keep old commits for ~30 days, but:

- they only exist in your reflog

- other clones can’t recover them

3. Trust issuesh3

If someone commits something in “2004” while your repo was created in 2023…

…it’s obvious history was manipulated.

4. Security concernsh3

Backdating commits = fabricating a timeline.

Not great for:

- audits

- IP claims

- compliance

- legal disputes

Practical Tip

If you’re on a team, agree on a policy:

- some teams love clean rebased histories

- some prefer: “never rewrite anything, ever”

Neither is wrong — they’re just different philosophies.

Why GitHub Verified Badges Disappearh2

When I pushed my rewritten commit, I noticed something else:

All the previous commits lost their Verified badge.

Why?

✔ Rewriting removes signatures

--amend creates a new commit object without the signature.

✔ GitHub verifies email ownership

Batman@rich.com does not belong to any GitHub account.

✔ GitHub verifies cryptographic signatures

Rewriting = signature gone = badge gone.

Can You Get Verified Back?h3

Yes — but not for Batman.

You can regain the badge if you:

- use your real GitHub email

- re-sign the commits with GPG/SSH

- or restore the original signed history

Rewritten commits = new hashes = new signatures needed.

What I Learnedh2

This experiment taught me more than expected:

- Git metadata is fully editable

- Dates can be literally anything — even before you were born

- Changing metadata = changing commit hash

- History rewriting instantly removes GitHub verification

- Git trusts developers more than developers trust Git

- GitHub will reflect whatever absurd story you feed into Git

Most importantly:

Git history is not immutable. It’s editable, malleable, forgeable — if you know how.

Final Thoughtsh2

This whole journey started with a stupid argument. It ended with me diving deeper into Git internals than I ever planned.

But honestly?

It was fun as hell.

If you’re curious about Git, try rewriting history in a test repo. You’ll walk away with a deeper understanding — and newfound respect for force pushes.

And if someone confidently tells you that Git history is immutable, maybe suggest a friendly bet.

Thanks to @suraj-kadapa for the bet that started this whole experiment.

Comments